|

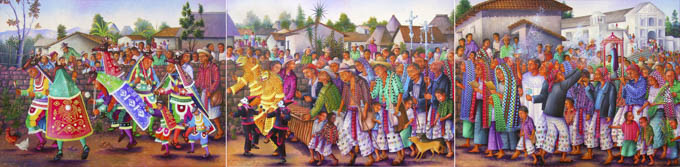

Footsteps of Yesterday and Today by Pedro Rafaél González Chavajay, 2001.

Huellas de Ayer y Hoy

Maya Social Organization Expressed in Art

The triptych Huellas de Ayer y Hoy, or Footsteps of Yesterday and Today, depicts a procession in the festival

of San Pedro la Laguna, which takes place on June 29, the feast day of the town’s patron saint, San Pedro (Saint Peter). The

triptych shows how the town and the procession would have looked in the middle of the twentieth century, a few years before

Pedro < was born.

The division of the painting into three parts represents the disintegration of Maya traditions and culture since 1950. Each

panel represents one part of Maya culture where the imposition of the invaders’ religious and political organization occurred:

pre-Hispanic traditions, church, and government. This reflects society’s new integration under the Catholic Church and the

hybridization of Maya spirituality and culture. Of course, this entailed the disintegration and rejection of many practices,

such as dances, among other significant elements of the Maya culture.

Now, however, each function completely independently. You no longer see a procession that is accompanied by traditional dances

of the community; there is no longer a relationship or coordination with the Church and the municipal government. Now the masked

dancers act through a sponsorship by some family or private groups that support these dances in the streets of the municipality.

The society of San Pedro is no longer a whole, but is divided into three parts, as represented in the triptych panels, where each

one symbolizes a change in the town.

|

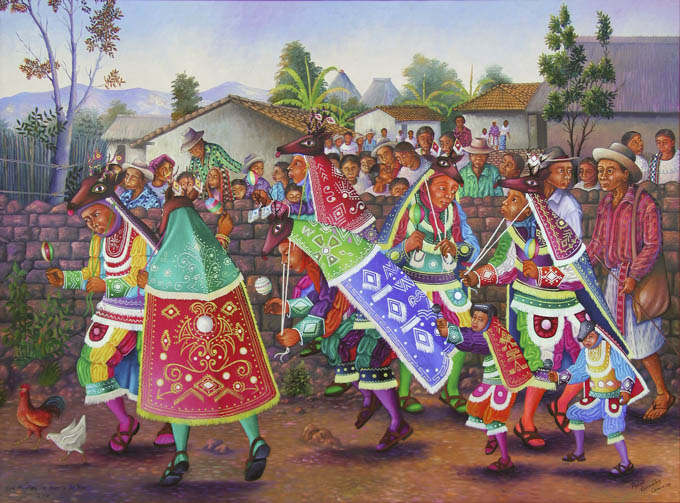

Panel 1: Pre-Hispanic Traditions

The left panel of the triptych shows dancers dressed as deer heading the procession. Pedro Rafaél, realizing the visual

importance of the dancers to the painting, has allowed the other dancers, dressed as tigers and monkeys, as well as the musician playing

the marimba, to straggle over into the first half of the second panel. This is artistic license and does not really detract from his

concept of the triptych showing the fracturing of Maya society.

The dance depicted is the Baile de Venado, or Deer Dance, but it could just as easily have been one of the other popular masked dances

such as the Dance of the Conquest, the Dance of the Moors and the Christians, or the Little Bull. The

Baile de Venado is one of the

oldest of the dances and has pre-Hispanic roots.

After the arrival of the Europeans, many dances were forbidden by the Catholic Church because they were deemed heathen. The dances that

did survive had to conform in some way. Performing the Deer Dance for the day of the patron saint of the town, and dedicating the captured

deer to Jesus, made the dance nominally Christian. It allowed some ancient Maya beliefs and traditions to survive, somewhat adjusted,

under the cloak of Christianity. In other towns, the text of the

Baile de Venado is different. In Tz’utujil towns such as Santiago

Atitlán and San Pedro, it is a story of the hunt, or the myth of creation or birth.

The effort that the person makes to participate in the dance signifies the reunion with life and nature. This effort involves great expense

to rent all the masks and costumes, the maintenance of the family during the time that the whole process lasts, and the performance of the

dance. Thus this effort also has its time before and after, for the group of dancers and the family of each of the participants.

Because of the effort and expense, especially in the smaller towns, the masked dances usually are only performed during the festival of the

town’s patron saint. The most elaborate and expensive of the dances is the Baile de Conquista (Dance of the Conquest), so in smaller towns,

which San Pedro was at the time, the Deer Dance was a popular alternative. Preparation for the dance began many months before the feria titular

(town festival). The person responsible to produce the dance was the director, someone knowledgeable about the contents and steps of the

dance. The director was responsible for choosing which dance will be performed, who the dancers will be, and for gaining support and funding

among the townspeople.

The rehearsals were held at the director’s house, or at the house of a particular cofradía. This involved considerable expense, as food and

beverages must be provided for the dancers. The town would hire a dance master, although sometimes the director and dance master might be

the same person. The dance master would thoroughly know the dance so that he could teach the performers their roles and their lines. For

this the dance master had to know how to read and write. He was owner and guardian of the script, which was used to teach their lines to

each of the dancers, most of whom were illiterate. The dance master also taught them the dance steps that go with each of their songs.

Because the dance master was paid for his services, he carefully guarded his manuscript. A dance master would probably train a son to

inherit his position and pass on his manuscript to him. For a complicated dance like the Baile de Conquista, the dance master might come

from another town, and serve as the dance master of this dance in several communities (Bode 1961).

The masks and costumes are rented from a morería, an establishment peculiar to Guatemala. It is usually run by a family of talented mask-makers

who pass down the business from generation to generation. When the time of the festival is approaching, the dance master and all of the members

of the dance troupe travel to the morería to rent the costumes. Before the Pan American highway was constructed, this meant a walk of about two

days each way to the town of Totonicapán, the nearest morería to San Pedro la Laguna. As shown in the painting, the deer, in costumes rented

from the morería, wear fanciful versions of the elaborate capes worn by the Spanish. These flashy costumes are often satin and decorated with

sequins and bits of mirror. Undoubtedly, the ancient Maya dressed in the skins of deer for the dance. While dancers in some towns still wear

deer skins, the dancers and spectators seem to prefer the costumes rented from the morerías. This is not surprising because the isolation of Maya

towns meant the dances were the highlight of the year (Luján Muñoz 1987).

One of the very important events for the organizer and the group of dancers, is to ask permission for the beginning of the organization of the

production. This may occur once or twice before the performance. The dance group would go to a sacred place in the mountains, generally a cave,

and the person in charge of the offering is an ajq’iij or spiritual guide who would perform a blessing so that the production could start and

finish well. During the ritual they would call on the four cardinal points, burning colored candles and incense, while offering sugar, cakes,

and chocolate to the spirits of the earth, sky, and lake. Upon their return from the morería with their costumes, a last ritual would be performed

in the mountains with much ritual drinking to induce a trance.

|

Panel 2: Town Elders, Municipal Government

The second and third panels of the triptych deal with the local government and the Catholic Church. The church and state of San Pedro and

all other highland Maya towns at that time were intrinsically intertwined in a civil ceremonial system. In the middle panel of the painting, the man

between the two crosses is the mayor of the town. He carries in his hand a baton that is symbol of his office. Directly behind him we see the head of

a man wearing a distinctive red or su’t (headscarf), which is an indication that he is one of the principales (high-ranking elders) of the town.

When anthropologist Benjamin D. Paul arrived in San Pedro in 1940, the civil ceremonial system was still strong and the cofradías still active. He says,

(Paul 1989, 1) it “…was a marvel to behold. The product of countless years of operation, its organization was intricate and neatly articulated. And it

served a host of significant functions for the individual and the community.” Under the cofradía system, about every four years men were expected to

devote all or part of their time to public service. The terms, which lasted for a year, would alternate between the church and the municipal government

of the town. During the year of service, their responsibilities would be handled by other family members, so they could devote themselves to the needs

of their office. As a person aged, he served in positions of greater importance, and with these positions came greater respect from the community.

On the civil side, Benjamin Paul counted 35 positions, among them alcalde (mayor), five regidores (councilmen), a síndico, a policía, first and second

mayores (constables), interpretes (people who spoke both Tz’utujil and Spanish), twelve alguaciles (errand men), and twelve regidores auxiliares who

rowed the large wooden municipal canoe that went daily between San Pedro and Santiago Atitlán (Paul 1989). The alcalde would be chosen by the town’s

principales—men of the village who were present or past heads of the six different cofradías. This system, in which the alcalde was chosen by people

who had served in the religious cofradías, kept the government of the town and the church intertwined.

In the 1940s, General Jorge Ubico introduced military training to the Maya towns. One result was that young men who went away to serve in the military

would refuse for a time to do servicio in the civil ceremonial system of the town when they returned. Then, in between the 1950s and 1970s, Protestantism

began attracting significant numbers of Maya. These Maya began refusing to participate in the Catholic cofradías, although they would still perform their

civil duties. During the 1950s when liberal Areval-Arbenz was president before being deposed by a CIA coup, it was decreed that the mayor and other town

officials would be elected by popular vote. Benjamin Paul observes, “At first this made little difference; the town was willing to confirm the slate

proposed by the principales in accordance with custom. But in time, competition between rival political parties arose, with the result that elected

officers were no longer part of a unified civil-ceremonial hierarchy.”

|

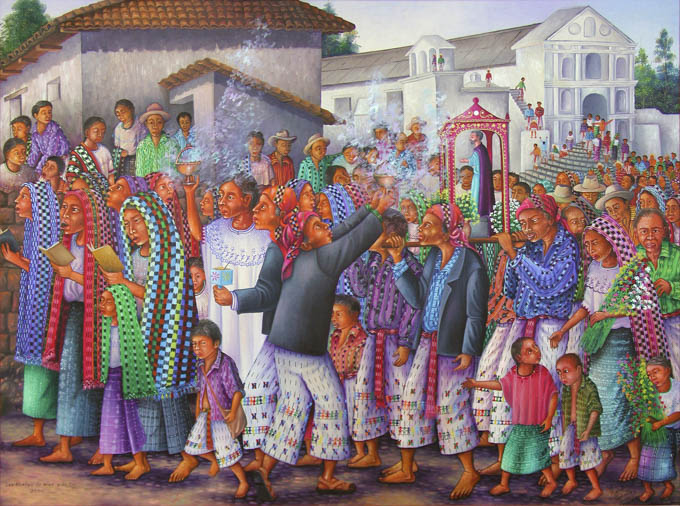

Panel 3: Catholic Church Traditions, Cofradías

In the third panel, the women singing are texeles (female members of the cofradía), followed by more principales with pom (incense) and

carrying the image of Saint Peter, who has been removed from his niche in the church for the procession. The cofradías are in turn followed by members

of the congregation.

Although Pedro Rafaél depicts nearly sixty people in the whole procession, each person in the painting represents several individuals. Each of the San

Pedro’s six cofradías would be represented in the procession.

The Imposition of the Cofradía Religious Brotherhoods

To fully understand the triptych Footsteps of Yesterday and Today, we must understand the past as well as the recent past. Particularly

important are the disintegration and fissures caused in the Maya cultural system by the imposition of the Christian religion. We must also understand

how society functioned throughout the centuries since the invasion of Europeans. The role of the cofradías, or religious brotherhoods, is a key element

in this process.

In the sixteenth century religious cofradías were introduced in Guatemala to help implement the Catholic faith. They quickly became popular. Because the

cofradías were strictly segregated (the Spanish had their own cofradías in Antigua and Guatemala City), the Maya found that in a cofradía they could continue

to perform many of their pre-Hispanic rituals in the name of a Christian saint. The Cofradía de Concepción was established in San Pedro on January 7,

1613 (Orellana 1984). To put that in a historical perspective, the first known cofradía was established in San Pedro 163 years before the United States

became independent from England.

Cofradía is a Spanish word that implies brotherhood, but both the cofradías and the civil government operate on a system that would better be called “fatherhood.”

As Benjamin Paul has explained many times, in the Tz’utujil language, if one is a male, there is no single term for one’s brothers. There is a term for one’s

older brothers, and another word for one’s younger brothers, and a word for one’s sisters. Likewise, if one is a girl, there is a word for one’s older sisters

and another for one’s younger sisters, and a word for one’s brothers. The language performs two functions: it helps establish a hierarchy (one does what one’s

older brother commands); and it also denotes a separation between male and female roles. This strict hierarchy also exists in the civil government and the

cofradías; i.e., the cofradías have a ranking of importance in relation to each other; and the members of each cofradía have a ranking within that cofradía.

(Paul 1989)

There were six cofradías in San Pedro. Each cofradía revered a particular saint. At the head of each cofradía, was a cofrade, whose assistant was called a juez;

five mayordomos; and three unmarried women called texeles or Te’xelaa’. An image of the saint was kept on an altar in a separate room in the house of the cofrade.

It was the duty of the cofradía to keep fresh flowers on the altar, and keep the floor covered with pine needles. The texeles ground castor oil beans from which

they obtained oil for a lamp that was kept perpetually lit on the altar. During the year, the cofradía would be responsible for a festival honoring their saint.

Each cofradía was responsible for one day of the week. They would be responsible for burying anybody in the community who died on that day. All these expenses,

which were considerable, would fall on the cofrade.

Protestantism attracted many Maya because it opposed drinking. Ritual drinking had been a part of the cofradías since their inception. Just as in other small

Maya towns, there had been no resident priest since the previous century, but only a visiting priest and local Maya who performed the services. Catholic Action

began sending resident priests in hope of reforming the church enough to keep members from leaving. Benjamin Paul observes (Paul 1996, 4):

The death blow to the weakened cofradías came in 1970, when the then resident priest, a Carmelite from Navarre, excoriated cofradía members from drinking

in church on Sunday, as they had done ceremonially from time immemorial, and denied them various customary privileges. In effect, they were excommunicated.

San Pedro once had a unified face it presented to the world. In the civil-ceremonial system the townspeople had a well-established way of gaining respect as they

progressed through life. If they earned the title of principale by the end of their lives, people would kiss their hands as a token of respect. The church and the

government functioned together as part of a whole.

Now, besides the Catholic Church, there are scores of fundamentalist Christian churches in town. Even in families considered progressive, children have been disowned

by switching from one church to another. The competition of political parties during elections has become rancorous, and occasionally violence has resulted

during the election process. The unified Tz’utujil Maya society has broken into the three separate parts represented by the three panels of Pedro Rafaél’s

painting: the masked dance, representing the pre-Hispanic Maya heritage, the government, and the Christian religion.

Bode, Barbara. 1961. Dance of the Conquest of Guatemala. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University.

Lujan Muñoz, Luis. 1987. Máscaras y Morerías de Guatemala/ Masks and Morerías of Guatemala. Guatemala: Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquín

Orellana, Sandra. 1984 The Tz’utujil Maya, Continuity and Change, 1250–1630. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

Paul, Benjamin D. 1989. “The Functions and Failure of the Traditional Guatemala Civil-Ceremonial System: The Case of San Pedro la Laguna.”

———. 1996. “Fifty Years of Change in San Pedro la Laguna.” (Paper presented on a panel at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association,

San Francisco, CA, November 1996).

|