The Maya Bonesetter

as sacred specialist

By Benjamin D. Paul, Stanford University

Among the dozen Maya communities that ring the shores of Lake Atitlán in the northwestern highlands of Guatemala,

the town of San Pedro la Laguna is perhaps the most enterprising and progressive. A few decades ago the Pedranos,

with their own labor and initiative, built a road around the steep sides of a huge volcanic mountain. and by now

Pedranos own and operate two large buses and a dozen trucks each representing a capital investment of over $10,000.

these vehicles serve San Pedro and the surrounding region by providing efficient transportation to the coastal

lowlands and to the capital of Guatemala. For reasons of history and ecology each village in the area has developed

distinctive specialties (Tax 1937), and it can be said that in recent years modern transport service has become

one of San Pedro's specialties.

|

|

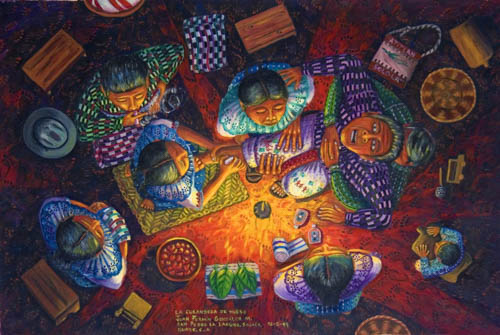

"La Curandera de Hueso," bonesetter. Arte Maya Tz'utujil has photographs of many paintings of "curanderos de huesos."

Many artists are not careful about getting details correct, such as having the "traje" (traditional attire) of the bonsetter

correct. Bonesetters are from San Pedro la Laguna, not Santiago Atitlán. Juan Fermin González is one of the few artists

who is very careful to get all of the details correct. Painting by Juan Fermin González Morales, 1999

Another Pedrano specialty of greater antiquity and of quite a different order is the traditional art of bonesetting.

In 1941, when we first began fieldwork. a healer named Ventura successfully treated a severe incapacitating ankle sprain sustained

by my wife on a rocky San Pedro path. Ventura was then 77, and since the turn of the century had been setting broken bones not only

for Pedranos but also for accident victims from many other parts of the republic and even from across the borders in El Salvador

and Mexico. A decade later Ventura died. and a few years after that his daughter Rosario rather unexpectedly assumed the burden

of repairing bone injuries. Because of her good results and widespread reputation, the town of San Pedro continued to attract

sufferers from distant places. Rosario still practices today, but she is old and lacks the physical strength to mend some of

the more severe fractures. But she is now only one of five or six bonesetters practicing in San Pedro. This is quite a change

from the time old Ventura was the lone expert in a town of 2,000 people. The population of San Pedro now approaches 5,000,

but the number of native bonesetters has increased disproportionately.

From the outsider's point of view, the healer resets bones by means of adroit manipulation, massaging the area with marrow

extracted from beef bones, placing heated tobacco leaves against the bare skin, and applying a tight bandage. A splint of

cardboard or slats may be used to immobilize the injured area. But the bonesetters and their clients see the process differently.

In their view the work is not done by the human practitioner but by a special little hone concealed in the hand of the healer,

who locates the precise point of the break by passing the bone back and forth over the general area of the injury. When the

traveling bone finds the critical juncture it comes to a halt and stays clamped to the spot long enough to correct the break

or dislocation. In describing the behavior of the searching bone, informants say it generates a force like an electric current

that jumps in intensity when it reaches the injury, where it takes hold "like a magnet."

Any citizen of San Pedro can decide to become a carpenter or aspire to own a truck, but no one can simply choose to be a shaman,

a bonesetter, or a midwife (Paul and Paul 1975). To enter one of these sacred professions the individual must receive a supernatural

call. To act on one's own initiative would be both ineffective and unsafe, the presumptuous individual would be stricken with death

or misfortune. And so would the person who receives the summons and refuses to heed the mandate. The channels for communicating the

divine will are multiple and marvelous. In his old age, Ventura recalled how he was induced to be a bonesetter. His story illustrates

the complex process of persuasion.

|

|

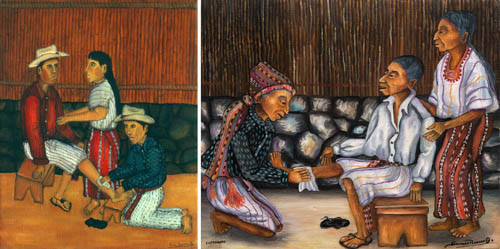

"Curandero," healer. Two paintings done by the same artist, with the same title and the same theme. The painting on the left, done

in 1987, while considerably more naive, is more accurate because the curandero wears the traje from the correct town. The curandero

wears the traje of San Pedro la Laguna, while the one on the right wears the traje of Santiago Atitlán, the town were the artist lives.

The traje of men of the two towns is similar, but the men's pants in Santiago end just below the knee and have stripes, while the men's

pants in San Pedro go to below the ankle and have black dashes rarther than stripes. In both paintings the woman and the patient wear

the traje of Santiago Atitlán. Paintings by Salvador Reanda Quieju, 1987 and 1990.

The Call of the Bone

Not long after marrying at age 20, Ventura had a strange dream. A bone was hopping about. He woke up worried and went off

early as usual to work in his distant cornfield. As he neared his destination he saw a curious object in the distance which turned out

on closer inspection to be a very shiny bone. The bright object leapt toward him. He drew back in fright, but it jumped in his direction

again, and then again. Fearful, and finding his way blocked, Ventura returned home, disguising the cause of his embarrassing retreat by

feigning illness and going to bed.

During the night he had another curious dream. This time the visitor was a dwarf who asked Ventura, ''Why didn't you pick me up? If you

go on refusing you will die.'' In the morning he arose determined. On the way to work the bone reappeared. Again it jumped. This time

Ventura was not afraid. He picked up the object, which measured an inch in diameter, wrapped it in his kerchief, and tucked it into

his sash. On the way back he felt it move about. At home he put it in a shoulder bag and hung it in a corner. He did not know the

bone's purpose, but instructional dreams followed. The same little man told Ventura that he was destined to aid humanity by caring

for the afflicted, ''because they are our children.'' The dwarf taught him a secret song, and at night Ventura would sing it.

In a dream one night the dwarf appeared with a skeleton. He handed Ventura a whip and told him to strike it down. Ventura obeyed and

the skeleton collapsed into a heap of bones. Then the dwarf ordered him to put the skeleton back together, threatening to whip him if

he failed. Ventura protested, ''Señor, I cannot.'' The dwarf then said, ''Where is the bone I gave you!'' Ventura fetched the bone he

had found on the path. With its help he began to recognize the different parts and to rebuild the skeleton, starting with the little

toe bones and proceeding to the bigger bones. When Ventura had reconstructed the entire skeleton under the guidance of his magic bone,

the dwarf said, ''With this bone you will cure our children." Ventura still did not know just what he was to do, but he kept receiving

instructions.

Ventura treated his bone with respect, placing it in a box of its own. When he closed the box he got on his knees and could hear the

object making sounds as of people talking inside. He took it out, wrapped it in a silken cloth, blew on it repeatedly, and replaced it

carefully. He was told never to let anyone touch the bone or else he or his children would die. The bone told him to guard it well because

" I have work to do." The bone announced that Ventura's young wife would give birth to ~ boy who would die. A boy was born and lived only

a short while. Ventura experienced other misfortunes. He fell to quarreling with his wife, who expressed fear that because of his fortuna

all their babies were destined to die. He replied that his call came from no human source but from God, that its true purpose was to give

life, that they would live better and live longer on earth. but he made no use of the bone for a year. Meanwhile he got sick; his head

and his heart began to ache, and he was on the point of death. Only by becoming a healer did he regain his health.

A boy he knew had broken a leg. In a dream the dwarf directed Ventura to use the bone. He complied; the break was mended and in three days

the boy was able to walk again. Ventura told no one what he had done, but word spread and his practice grew. He never charged for his services,

leaving it up to his patients to donate what they wished or to give nothing at all.

Some of the details of Ventura's experience are unique, but a comparison of his story and those of the other San Pedro bonesetters discloses

a common pattern. The candidate encounters a small bone-like object that moves and he is instructed in his dreams to pick it up. He puts it away,

and for a period of time, which may be short or last many years, he fails to act on any cryptic messages he receives. He usually suffers for

this in some way until he begins to exercise his calling. He is trained by no one, only in dreams is he told how to cure, and in any case it

is the secret bone that does the work. Since bonesetting is a hallowed duty the practitioner must not charge for his service.

|

|

"Curandera," healer. In this painting both the "curandera" and the patient wear the "traje" of San Pedro la Laguna. Painting by

Domingo Garcia Criado, 2007.

Bonesetters earn little income from their part-time curing specialty in this money-conscious community. Sometimes they are called

to attend an accident victim in another town, staying with the patient for several days or weeks in Chimaltenango or Antigua or wherever it may

be. They receive meals and transportation costs and perhaps "unos centavitos,'' but it is difficult to see what they gain for their time and labor

beyond the satisfaction of knowing that they are carrying out God's humanitarian purposes and perhaps gaining a certain amount of immunity from

accidents themselves. One bonesetter, who also heads a marimba band that travels to many towns, remarked significantly that he was in four road

accidents without ever being injured.

Another bonesetter, who is also a leading midwife in San Pedro, had just been incapacitated with two injured ankles when word arrived that one of

her patients was about to give birth. Despite her husband's protests she insisted on going out, and was about to walk after hastily doctoring her

own ankles with the aid of a curing bone she had found long ago and had stored away without realizing its significance. The success of this

emergency action launched her practice as a bonesetter and changed her luck. Previously prone to slipping and spraining her ankles, she now

became nimble and sure-footed.

While all healers claim they acquired their special knowledge in dreams, their dream experiences differ in content and degree of specificity.

Ventura had rebuilt the skeleton from the feet up; one of the newer bonesetters recalls beginning with the cranium and ending with the legs and

feet. Others do not mention such a dream test at all. The man in Ventura's dreams was a dwarf. In another case he was a very large ladino with a

beard, dressed completely in white from head to shoes. In the neighboring town of San Juan, which is nearly a suburb of San Pedro, a man destined

to be a bonesetter was visited by someone he described as ''a dwarf dressed in white like a doctor and with a suitcase'' (Rodriguez Rouanet 1969:68).

One Pedrano bonesetter described the visitor as a boy dressed in ladino clothes. Still another received his message from one of the two angels

that guard Jesucristo. This same informant said that when he sets bones he begs forgiveness (pedir un perdón) just as Jesus did when he stumbled

under the weight of the cross he was carrying.

The Zutuhil phrase describing a curer with supernatural connections is k'o rxin, meaning he or she has the gift, and the gift is understood as

referring equally to the charismatic quality of the healer and to the object that embodies his power. In Spanish reference the power object,

the bone in the case of a bonesetter, is variously called the healer's suerte, fortuna or virtud. Bonesetters sometimes refer to the object as

their instrument (aparato, materiál) although in their conception the mystic bone is the healer and its possessor the instrument.

|

|

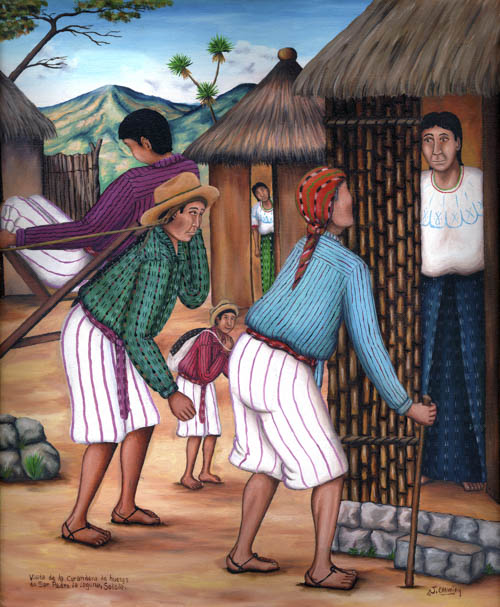

Visita de la Curandera de Huesos, San Pedro la Laguna, Sololá," visit to the bonesetter in San Pedro la Laguna in the department of Sololá.

Before cars and trucks were common in Maya towns, men would strap a chair to their back to carry an injured patient to the healer. Painting

by Juan González Chavajay, 1988.

The bone can alert its owner by moving or making a sound when a serious fracture occurs somewhere. Unaided, it can hop out of

its box into the curer's shoulder bag or the folds of his sash when he leaves the house to travel or work in the field. If the owner drops the

bone while mending a fracture, it can bring death to the patient. It can make itself invisible; a stranger might be looking directly at it and

yet not see it. It can assume the guise of a man. It can disappear, as Ventura's bone did after that celebrated bonesetter died.

Normally the special objects belonging to sacred curers--shamans, midwives, bonesetters--accompany them in their coffins when they die. But according

to Rosario, Ventura had a vision before dying that Rosario one day would become a bonesetter and that the bone should be kept in its usual box.

Somehow it came into the possession of a man in San Juan who used it to cure his son's fractured limb, proclaiming that he had found his magic

bone He attracted patients and charged very high fees. This displeased the bone, and in a few weeks it came to Rosario in a dream. The bone told

her it had returned because it was displeased by the Juanero's unconscionable behavior and would now remain with Rosario all her life. It said she

was to become a bonesetter like her dead father and never charge for her services. In the middle of the night Rosario heard a noise and thought

someone was tampering with the box that had belonged to her father. When she examined the box, she found the bone back in its usual place. She

burned incense and two candles. Later, she had dreams and eventually, despite delay and reluctance, became a bonesetter, but only after a series

of increasingly severe illnesses.

The bonesetter's bone is a sacred object, surrounded by taboos and credited with miraculous abilities. It is a repository of supernatural power,

a potent cultural symbol binding patient and practitioner in a bond of faith and assurance. It partakes of the same mystique that draws pilgrims

to the site of an enshrined relic. As a sign of the bonesetter's accreditation, it is the equivalent of the doctor's diploma. Like the secular

physician, the Pedrano bonesetter uses his hands to straighten fractures, however he may interpret the source of his dexterity and clinical

judgment. In this respect he differs from his counterpart in Zinacantan where the most highly regarded bonesetters are those who ''use prayers

and other spiritual methods exclusively" while ''a bonesetter who actually sets bones is considered far inferior" (Fabrega and Silver 1973: 41-42).

In the native view, the bonesetter's medicine works because his bone is a conductor of supernatural forces. For Pedranos the manifest message of

the magic bone is that religion empowers medicine. But the latent message reads in reverse: medicine empowers religion. Each instance of curing

in the material world recharges faith in the existence of the spiritual world. Pedranos admire material progress. Tired of foot travel and back

packs, they value the efficiency of trucks and buses acquired in increasing numbers. But greater mechanical efficiency brings greater human hazards.

With more trucks there are more accidents and more need for bonesetters. If setting bones is seen in progressive San Pedro la Laguna as a sacred

office, this may be because the very nature of the art--making broken parts whole--so graphically symbolizes and satisfies a profound human yearning

to transform disorder into order, to convert chaos into cosmos.

|

|

"El Curandero, Atitlán," the bonesetter Santiago Atitlán. The bonesetter's "raje" in this painting is not correct. He should be depicted

wearing the "traje "of San Pedro la Laguna. He would have traveled to Santiago Atitlán, or the patient would have traveled to San Pedro la

Laguna. About this inaccuracy the artist said that the tourists are more likely to buy the painting if the "traje" is of Santiago Atitlán.

It is more likely that the galleries, most of which are in Santiago Atitlán, are more likely to buy the painting from the artist if the

"traje" depicted is Santiago Atitlán. Painting by Antonio Coche Mendoza (from San Juan la Laguna), 1990.

Bibliography

Fabrega, H. Jr., and D B. Silver. 1973. Illness and Shamanistic Curing in Zinacantan. Stanford.

Paul, L., and B. D. Paul. 1975. The Maya Midwife as Sacred Professional. American Ethnologist 2: 707-726.

Rodriguez Rouanet, F. 1969. Prácticas médicas tradicionales de los Indigenas de Guatemala. Guatemala Indigena 4(2): 51-86.

Tax, S. 1937. The Municipios of the Midwestern Highlands of Guatemala. American Anthropologist 39: 423-444

|