Antonio C. Ixtamer

By Joseph Johnston

The Maya who become artists will all tell you that they excelled in drawing when

they young. Antonio Coche Ixtamer was no exception. His life was typical of a poor Maya campesino

family. He helped his father in the fields, often getting up at four in the morning to work before

going to school. For Ixtamer the big event in his childhood was when his father had enough money to

buy him his first pair shoes so that he no longer had to go barefoot.

Attending the only art class in the bilingual public schools in San Juan la Laguna inspired Ixtamer’s

interest in painting. This class for older students was taught one afternoon a week by San Pedro la Laguna

artist Pedro Rafaé González Chavajay. In around 1986 when Ixtamer graduated from school, he convinced his

father to pay for painting lessons on weekends with Pedro Rafaé. For six months Ixtamer drew faces until

he satisfied Pedro Rafaé that he could draw well. Only then was he taught to mix colors, apply paint,

and make small copies of paintings Pedro Rafaé himself was working on.

|

|

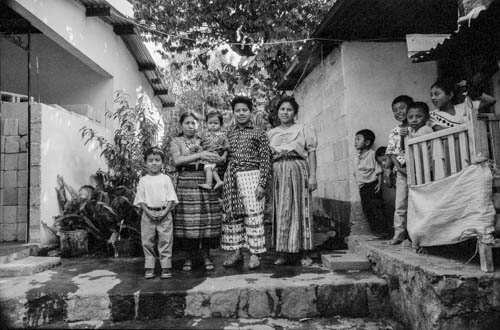

Antonio Ixtamer pose for a photograph with his wife Anna, his mother, and his two children

in the early 1990s. At this time having your photograph taken was a big event, and the neighbor children watch,

unaware that they are also in the photograph. Ixatmer's baby daughter is now grown and has a presence on Facebook.

After studying with Pedro Rafaé intermittently over the course of two years, Ixtamer began

painting on his own, selling his canvases to galleries in Santiago Atitlán. Ixtamer’s carefully painted themes

did not earn him enough money to live on, because the Santiago galleries wanted inexpensive quickly-produced

pictures to sell to tourists. Not only Ixtamer, but all Tz’utujil artists trying to sell paintings to the

galleries in Santiago Atitlán have found that the tourists want small mementos from Guatemala to give to

friends when they get home, not fine works of art. These galleries, because tourists are almost their entire

market, try to buy the works as cheaply as possible. The quality of the work sold in the Santiago Atitlán

galleries and the price paid to the artists has continued to diminish almost every year.

A woman from the United States named Lianna Ward, who had started a women’s weaving cooperative in San Juan,

liked Ixtamer’s paintings and wanted to help him. She showed his work to Jim Bell, another U.S. citizen who

had a gallery in Antigua Guatemala. Ixtamer received a telegram from Jim Bell telling him he wanted his paintings.

This was a big event. Who else in his neighborhood had ever received a telegram? He now had a gallery to sell

his paintings. In 1990, after having exhibited and sold Ixtamer’s paintings in Antigua for about a year, Bell

grew ill and suddenly died. Bell’s family removed everything from the gallery not knowing that Ixtamer’s paintings

were on consignment. When Antonio next traveled to Antigua, he found the gallery closed and his paintings gone.

Questioning the neighbors, he learned that his patron was dead. Discouraged, he stopped painting.

In 1987 when Ixtamer was studying with Pedro Rafaé at his house in San Pedro, I was briefly introduced to the

would-be artist. A year later, having forgotten Pedro Rafaé’s student, I entered a gallery in Santiago Atitlán.

The wall was filled with small inconsequential paintings, but among these were several paintings with especially

beautiful colors. Although they were randomly distributed, I noticed that every one of the good paintings was

signed “AC Ixtamer.” After I chose one to buy, Diego Chavez, the gallery owner, asked if I wanted to meet the

artist. It turned out that Antonio Ixtamer had brought the paintings to the gallery and they had just finished

putting them on the wall when I arrived. He had secretly watched as I chose his painting from among the hundreds

on the walls.

|

|

Antonio converted part of the front room of his house into a gallery. Photo: Joseph Johnston, 1995.

When I returned home to California, this painting’s beauty entranced me. I wanted to meet the artist. My

woodcarver friend, Vicente Cumes Pop, arranged for me to visit Ixtamer during a trip to Guatemala in 1991. Ixtamer, on being

told that a gringo wanted to visit him, finished a painting that he had been working on before the death of Jim Bell. He

hadn’t been painting for over a year. Vicente and I, after viewing the few paintings he still had at his house, urged

Ixtamer to take up painting again. I bought the painting he had finished, Pascual Abaj, and another which had

languished at a local co-operative seldom visited by tourists.

Once again encouraged and with money to buy supplies, Ixtamer completed a couple of new paintings within a few weeks and

walked to San Pedro hoping to sell them to Clement Puzul who ran the only art gallery in San Pedro la Laguna. Clement was

not at home, and Ixtamer, discouraged, sat down on the stoop of a nearby house to rest. Unbeknownst to Ixtamer, he had

chosen the stoop of the house of Vicente Cumes. Vicente noticed Ixtamer and invited the young artist in. By chance Vicente

had just earned a little money and decided to buy the paintings to encourage Ixtamer.

|

|

Amtonio and Anna in their garden.

Ixtamer clearly had skill in applying paint to the canvas and had an excellent eye for color. His themes,

however, were often ordinary. Vicente and I came up with a plan to help the young artist and inspire him to do finer work.

Vicente would buy Ixtamer’s paintings for me, giving Ixtamer a ready market for his paintings at a better price than he could

ever get in Guatemala. By walking to San Juan to visit Ixtamer every couple of days, Vicente could also oversee the artist’s

work and offer him advice on how to improve it. Vicente, being a woodcarver, had a number of original themes in his mind which

he had been saving to execute himself. He decided to give four of these themes to Ixtamer, starting with the easiest and least

important. The idea was to test Ixtamer to see if he had the desire and ability to become a better artist, incorporating Vicente’s

suggestions into his paintings. If Ixtamer did well with these four themes and responded positively to Vicente’s advice, he

would continue working with the young artist.

The first of these themes was La Cena del Campesino. It was followed by Emigracion, Sololá, Día de los Reyes, Sololá, and

Retorno de los Refugiados. When asked, Vicente always tells artists the truth about their paintings. This bluntness makes most

artists (who would rather be praised for their last work rather than hear how they could make it better) avoid Vicente. Vicente

pushed Ixtamer hard, and surprisingly Ixtamer responded well to Vicente’s encouragement and criticism. Before Ixtamer started

working with Vicente, he was just one of a number of competent young painters who had sprouted up in the Tz’utujil communities.

After he had completed the four themes given him by Vicente it was clear that Ixtamer had emerged as a significant Tz’utujil

Maya artist.

|