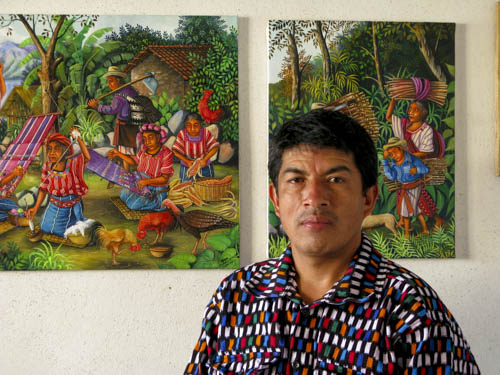

Mario González Chavajay

By Joseph Johnston

Mario is probably the hardest-working of the Tz’utujil Maya

artists. He starts painting early in the morning and seldom stops

until it is dark. He paints every day. One of Pedro Rafaé González

Chavajay’s younger brothers, Mario learned to paint on his own, with

little help from his older brother. As a result, their styles of

painting are very different. Mario is one of the first five artists

to whom Vicente Cumes introduced me. At that time Mario had several

tiny paintings in his studio which he had painted to sell to the

galleries in Santiago Atitlán. I did not really like any of them

very much, but he seemed so desperate to sell me one that I bought

the least objectionable one. He received 25 quetzals for it, a sum

which at that time would be equivalent to about five U.S. dollars.

Twenty years later he told me that my purchase was a life-changing

experience for him. For the first time he had sold a painting to a

tourist and had received about five times what the galleries would

have paid him. With the money, he bought oranges in the market for

his mother, a rare treat for a landless campesino family.

I continued to visit Mario every time I came to San Pedro.

He always seemed to be in a desperate situation financially complaining

that no one bought his paintings. I occasionally bought a painting from

him even though I did not like his colors, which seemed muddy. Mario did

not pay the same attention to detail as the three Hermanos González Chavajay did.

|

|

Mario González Chavajay with his wife. Through hard work and persistence

Mario has become known as one of the best artists in San Pedro.

On a visit in 1999, I noticed that his colors were stronger and purer, and

the people were more carefully painted. Mario had been churning out paintings

for the galleries in Santiago Atitlán for about ten years. He could paint about

one 9” x 11” painting a day. The galleries paid him more for his paintings

than they did to other artists because his paintings sold better to tourists.

Mario complained to me, however, that this was a dead end street. It bored him

turning out endless versions of the same ten or so themes that the galleries

wanted to have constantly replenished. When he painted an original theme, it

would take him three days to do a painting instead of one, and he would

receive no more from the galleries for this painting. Worse still was the

fact that the next time he visited Santiago Atitlán, he would see copies of

his painting done by the other artists. I therefore asked him to paint me two

original themes, and I would buy them at a fair price for his work and time.

Pleased with the resulting paintings we started working closely together.

In one of Mario’s large paintings, a particularly beautiful depiction of sugar

cane leaves inspired me to suggest that he feature more foliage in his paintings.

I thought that the leaves and flowers of many Guatemala plants would seem exotic to

people who did not live in the tropics. Mario jumped at the idea and began painting

scenes of Maya people in forests and jungles. Previously, most of Mario’s paintings

were night markets or interiors in which women were cooking or weaving. This new

direction in Mario’s painting, coupled with his improvement in color and detail,

suddenly set his work apart from other Tz’utujil artists. After years of struggling,

Mario had found his own style, however, a style still within the Tz’utujil style painting.

|