Chapter Two

Juana, a Prototypical Midwife

Juana, who was 51 in 1975, has been practicing for 15 years. She is the most popular midwife and has the largest clientele.*

By Pedrano standards she is the "ideal" midwife, comely, virtuous, quiet-spoken, self-assured, competent, dignified, and compassionate, with

indisputable supernatural credentials, and by now her skill in dealing with difficult deliveries that other midwives have given up as

hopeless has become legendary.

Juana is the second of six surviving children. Maria, her older sister, was born after three children died in infancy. Juana's mother

came from a wealthy Indian family. Her maternal great-grandmother was a midwife. Juana's father, a shaman who specialized in curing insanity,

came from a poor family. However, he' strategically married Juana's mother and, by agreeing to uxorilocal residence, took over the management

of his wife's estate.

*Of a total of 203 San Pedro births in 1973, Juana delivered 72, or 35%. Her closest rivals delivered 57 and 32 cases,

respectively. The remaining 42 cases were delivered by four midwives.

|

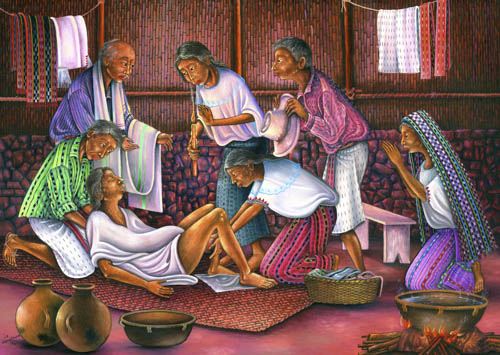

"Parto," childbirth. Painting by Mario González Chavajay, 2009. Collection: Arte Maya Tz'utujil.

Juana is the second of six surviving children. Maria, her older sister, was born after three children died in infancy. Juana's mother

came from a wealthy Indian family. Her maternal great-grandmother was a midwife. Juana's father, a shaman who specialized in curing insanity, came

from a poor family. However, he' strategically married Juana's mother and, by agreeing to uxorilocal residence, took over the management of his wife's

estate.

When she was growing up, Juana was modest, obedient, and respectful, mastering the required feminine skills of grinding and weaving, in contrast to her

older sister, who was recalcitrant, "lazy," and constantly at odds with her parents. Unlike Maria, who was "temperamental," Juana was quiet and would

sometimes sit in the doorway just "gazing off into space" while she embroidered her father's pants. Her mother never disturbed her when she found her

doing this. Daydreaming is generally discouraged, but children with special destinies are permitted, even expected, to show early signs of their

presumed mystical tendencies. Nothing was ever said explicitly to Juana concerning her destiny, for to speak or boast of it might bring death to

the girl from the supernaturals or from the envidia (envy) of other Pedranos. Furthermore, parents fear that if word got around their daughter might

not get a husband. For what young man will court a girl who is to become a midwife?

On more than one occasion Juana, as a child of destiny, was taken to a shaman by her parents to have protective costumbres (rites) performed for her.

In the church, candles were burned and prayers were addressed to Santa Ana, chief of the "twelve Marias," the patron saints of childbirth. Under cover

of darkness, the party would secretly go to native shrines on the outskirts of the village. Here candles, incense, and rum were offered by the shaman

to the ancestral spirits of former San Pedro midwives, to other ancestor spirits, and to the supernatural lords of the many domains of nature and of

calendric time.

Periodically, Juana observed the midwife who visited her own mother. Around this woman, called iyom in Zutuhil-Maya, there was an aura of awe and suppressed

excitement. But Juana and the other children were told only that a new child had been "bought" from the extranjeros (foreigners). Whenever the iyom appeared

everyone would kiss her hand respectfully, as they now kiss Juana's. One time the midwife put her hand on young Juana's head and told her she too would

be an iyom one day, but it would be a long time before the child knew what meaning to attach to the word.

Juana repeatedly had enigmatic dreams around her twelfth and thirteenth years. One of these dreams resembled what Eliade (1964) calls the "ecstatic journey"

characteristic of shamans. "In my dream an old man, all in white, with white hair and white beard, appeared," Juana recalls. "He tucked me under his arm like

a bundle. He held me tight and we flew far far away, just like birds, over many towns and strange places. No, I wasn't afraid. It was very beautiful. I looked

down from the sky and saw the houses like tiny toys down below. Everything looked so pretty. After a long time of flying, he brought me back."

Knowing nothing then of sex or reproduction, Juana says she felt both frightened and "strange" when she had a dream in which she saw a woman with her legs spread

apart, her skirt up, and a ''bloody'' baby coming out of her. "A woman all in pure white from head to toe handed me a white cloth and showed me how to receive

the baby." When she told her mother of the "funny sight—a baby emerging from its mother's anus," her mother only scolded her and sharply warned her never to

reveal her dreams. "Being a child, I naturally told my cousins the next day and got a hard beating when the story got back to my mother. She warned me that I

would die if I talked about it again." After that Juana kept her dreams to herself. Juana now interprets her early dreams as previsionary revelation of "primal"

mysteries of creation, as early evidence of her mystical vocation. Juana's mother and her culture made clear to her that her dreams were sacred, that to reveal

the forbidden mysteries she had seen could be fatal. She claims, as do all midwives, not to have understood the significance of her adolescent dreams until

much later when she was to become a midwife.

Other midwives similarly report having had dreams of childbirth and of ecstatic journeys around the time of puberty. This time coincides with the period when

courtship starts for most girls in San Pedro, a time of heightened sensitivity and self-awareness. But during the two decades or so of childbearing following

marriage, the mystical identity seems to recede into latency while the young woman is preoccupied with the usual transitions to adult roles and with the pains

and pleasures of every normal woman's life in San Pedro.

Unlike most other Pedrano girls of that period who chose to be "stolen" (Paul and Paul 1963), Juana did not run off with a suitor to his parent's house. Instead

she agreed to marry him only if he would live with her parents. Her husband's family had less property than Juana's but he too came from a family of some distinction.

His paternal grandfather and aunt were divinely chosen bonesetters, famous in distant towns as well as in San Pedro.

Juana's mother, on her deathbed in 1958, a year before Juana herself fell ill, revealed to Juana her own divine destiny, unfulfilled because of vergüenza (shame) and

fear of her husband's violent temper. She entrusted Juana's birth sign, the treasured piece of amniotic sac, to Juana's father, to be revealed at the proper time.

Juana says her mother died prematurely young because of her failure to exercise her own mandate to be a midwife.

|

"La Comadrona," the midwife. Painting by Pedro Rafael González Chavajay, 1996.Helen Moran

Collection: mayawomeninart.org

Juana had already lost six of her ten children when her mother died. For over a year she suffered weakness, shortness of breath, "heavy heart," a variety

of aches and pains-the classic symptoms of grief described by Lindemann (1944). Finally she was "forced to stay in bed," a rare event for stoically trained Indian women.

She was unable to eat or drink, grew weak, and slept only fitfully. She did not respond to pills, herbs, or prescription medicines. She lost weight, grew "thin" (wasted),

and began having strange dreams.

In her dreams Juana was visited by big, fat women, all in radiant white, who told her that she was sick and that her children had died because she was not

going out to help the women in childbirth. These were the spirits of dead midwives. When she tried to sleep, the spirits would appear. They would grab her

ears and scold her, tell her that she would die and her husband would die if she did not exercise her calling. They reminded her that she had already lost

six children. You were punished, they said, because you did not pay attention to those who gave you the virtud. Now, if you continue to hesitate your other

children will also die. Remember, they reminded her, that your mother died because you did not obey God's call.

When Juana protested that she was too ignorant and incompetent, that she knew nothing about the skills that a midwife must have, the spirits assured her they

would instruct her. They showed her the signs of pregnancy, how to massage the pregnant woman, and to· palpate the abdomen to feel if the fetus was in correct

position for delivery. They demonstrated "external version" (turning the fetus). In her dreams she saw graphically a woman delivering a baby. The spirits showed

her how to hold the white cloth with which to receive the fetus and how to clean the newborn infant. They showed her how to cut the cord and interpret its markings.

They instructed her not to cut the umbilical cord before the placenta was presented. They showed her how the umbilical cord must be followed back up to the placenta

in case it does not come out, and the placenta removed manually if necessary. They showed her how to "smoke" a woman with embers from the fire in such cases. They

told her they would always be present, though invisible, at deliveries to help her. The spirits instructed her how to bind the woman's abdomen after delivery to

"hold the organs in place." "All these things I saw," Juana says, and in addition, they taught her prayers and ritual procedures.

When she related her disturbing dreams to her husband, he protested. He did not want her to go about the village as a midwife, neglecting the household and their

children. Finally, he too fell ill and was visited in his dreams by the women in white. They scolded him, saying he must tell his wife to start practicing, or both

would die. Juana's father, in his capacity as shaman, was finally consulted about their dreams. He lit candles in the house, burned incense, and performed divination

rituals. He confirmed the warnings of the spirits and ceremoniously brought out the proof, the birth sign entrusted to him by her mother. Juana began to regain her

strength.

Shortly thereafter, as Juana was returning from the lake, a curiously shaped white bone about nine inches long suddenly skipped down the road before her. She was

frightened and dared not touch it. That night the women in white appeared again and instructed her to pick up the bone. They said, "This is your virtud, you must

keep it always, never show it to anyone, guard it carefully." The next day the bone reappeared in her path. She obeyed the spirits, and picked it up. When she

arrived home, the magic bone was no longer in her shawl but in her cabinet, already waiting for her. Soon afterward a small knife also appeared magically in her

path. This time she did not hesitate, but picked it up and carried it home. This she uses to cut the umbilical cord.

Finding her objects was the final sign. Juana's father urged against further delay. He performed nightlong costumbres this time, keeping Juana and her husband

on their knees for many hours. In the ritual rhetoric of shamans, he summoned and addressed the patron saints and the ancestral guardians of childbirth, the deities

of hills, waters, rains, winds, the masters and spirit guardians of all domains. He begged forgiveness for all the sins of Juana and her relatives, both past and

present, promising the supernaturals that Juana would fulfill their command willingly and with a good heart. He assured the spirits that her husband bowed to their

mandate and would give his wholehearted support to the selfless sacrifice she was about to make for the sake of the women of San Pedro. On the following day the

standard ritual gift for a shaman, a cooked chicken and a basket of tortillas, was sent to her father, now remarried and living again in his natal town.

On our return to San Pedro in 1962 we found that Juana, then 37, had been practicing midwifery for two years. Juana's reputation as a midwife was early enhanced by

her successful delivery of twins in a breech presentation. The case had been given up as hopeless by another midwife. Her career was a frequent topic of conversation

among Pedranos, both male and female. Her supernatural experiences and her "miraculous" obstetrical skills were already becoming legendary, recounted with dramatic

effects and in the lowered tones Pedranos characteristically use when speaking of native supernatural phenomena, as opposed to Christian deities. Blending new

elements with the traditional, Juana performs the special rituals for children born with divine destinies, as well as the rituals of purification that end the

eight-day postpartum period (Paul and Paul 1975). The combination of faith in her supernatural power, confidence in her medicine and new methods, and a relationship

based on trust seems to predispose her patients to experience relatively easy deliveries. Yet the concept of painless "natural childbirth" is unknown to her.

When one of her patients laughed and talked throughout labor and the delivery, Juana worried that the patient might be crazy.

Because a midwife may not become pregnant, Juana began using birth control pills in 1962. Two years later she was using an I.U.D. But for the last decade she and her

husband have not shared a bed. "How would it look" she says, if I, a midwife, went out pregnant to see my patients. A fine sight I would be! What a shame! And a sin!"

Moreover it could be dangerous for her patients, she adds. Once her case load increased to sizable proportions, she announced to her husband that she could no longer

sleep with him. "As a midwife, I must think first of my patients," she pointed out. Pedranos view sex as polluting, and therefore dangerous to the woman in childbirth.

Juana told her husband she would not blame him even if he left and refused to provide food and clothing for her and their children, but that she had no choice. She

even advised him to find someone else to satisfy his sexual needs. "Not an angry type of man," he agreed to her celibacy but pleaded with her for "just one more time,"

she recounted amidst gales of laughter.

In a sense Juana solved the problem of her relationship with her husband years in advance, by selecting the suitor who agreed to live on her home ground rather than

his. This gave her preferential treatment in inheritance and enabled her to acquire her own house and a unique measure of independence. It also ensured for her a

husband who was less concerned about his manliness than are the many Pedrano men who balk at uxorilocal marriage. But her husband's initial resistance to her career

was real, the resistance of a normal Pedrano husband, just as Juana's illness and suffering prior to practicing were real.

Juana's economic independence, her husband's own familial background and his regard for the sacred professions, the mix of their temperaments, all facilitated Juana's

final emergence as a full-fledged ritual specialist, but she was too successfully socialized as a normal woman to make the transition without a crisis of identity

(her illness).

|