As it was observed by the author in the year 1941.

Chapter One

The Childhood Period

A baby born in San Pedro is destined by his biological inheritance to show physical features marking him as an

Indian. But apart from physical appearance and conceivably a slight variation in temperament, the infant is no

more predisposed at birth to behave like a Pedrano than to think and act like a Frenchman, a Chinese, or an

American. However, all evidence indicates that the child will grow up to speak and act like his parents and

friends in San Pedro because of the particular set of circumstances that mold his development from infancy

to adulthood.

|

San Pedro girls with "tinajas" earthenware jugs that they balance on their heads while carrying water up from the lake.

Photo: Ben Paul, 1941

Though they elude recall in later years, experiences of infancy leave their imprint on the character of the

individual. Unpleasant treatment at the outset may affect his capacity to make a satisfactory social adjustment as an adult,

though this depends on the kind of culture or society in which he is destined to live out his life.

In general, infants in San Pedro receive good care and escape the frustration of adjusting to fixed feeding schedules and

the early demands for cleanliness characteristic of other societies. Babies are well clothed and rediapered frequently. By

day they sleep in a hammock, safely and comfortably, and at night they share their mother's bed. They are offered the breast

whenever they cry. If the mother is temporarily absent, an older sister or another woman of the household pacifies a child

by picking it up.

1. Adult Attitudes Toward Infants

Both men and women are indulgent and expressive in handling their babies. When time allows, a mother will sit

in the hammock, rocking the infant in her arms as she croons a lullaby. After resting on his return from the fields, a father

will play affectionately with his baby, bouncing it on his knee and laughing at its antics. Older sisters treat babies entrusted

to their care tenderly and share their parents' pride over the accomplishments of the child when it begins to crawl or to take

its first steps.

Many precautions are taken to protect the health of the infant. Some of these are practical, and some are based on superstitions.

People do not boast about children nor expose them unnecessarily to public view for fear of the "evil-eye." The infant is hidden

in the folds of a shawl when carried in the street. Its face is first publicly exposed when it is baptized in the company of other

infants, parents, and godparents who assemble in church to take advantage of the periodic visits of the priest.

Baptism is usually delayed until the child is about six months old. The reasons usually given for the delay are difficulty of paying

the fee or rarity of the priest's arrival in San Pedro. Actually, parents are reluctant to expose the infant to the crowd at the

baptismal font and hence to the chance of "evil-eye" before it is old enough to withstand the danger. Women school teachers temporarily

stationed in San Pedro are the most common choice for godmothers, since they are not Indians and are considered more worldly in

their knowledge.

Babies are introduced early to corn gruel and bits of tortilla, but they continue nursing until they are twelve or eighteen months

old. The usual reason for weaning is the advanced pregnancy of the mother. The milk is believed to be injurious to the nursing child

when the mother is in the fourth or fifth month of pregnancy.

As a rule the average mother gives birth to a baby every year and a half or two years. She bears from six to a dozen children. But

only half (or less) of this number survive, most deaths occurring in early infancy because of infection or other disease. Birth control

is not practiced, or at least not countenanced. Some couples remain childless, but these are considered unusual cases attributable

either to the "strong blood" of the wife or the unhappy coincidence of "weak blood" in both partners. The concept of blood strength

approximates what we might term strength of character or individual forcefulness. Fathers are said metaphorically to carry the fate

of their daughters on their backs, mothers to control the destiny of their sons.

Children of crawling age are carried about in a shawl rather than left for long periods on the floor where they are in danger of

upsetting pots, getting into the fire, or contracting dysentery and other illnesses from the dirt floor. They are aided in taking

their first steps but are not prodded into walking. No effort is made to instruct them in toilet training until they are old enough

to walk and talk. When they are two or three years old, they are encouraged to go into the yard when they feel the need. Later they

learn to use an out-house. Beyond occasional shaming devices, no punishment is used to hasten toilet training.

Everything considered, children receive benign treatment during their first year or two of life, enjoying the affectionate and permissive

handling now advocated by child psychologists in America. But secure infancy, by itself, is no augury of a model adult personality. Much

depends on the nature and tone of subsequent experiences in and outside the home and on the system of values and ideas communicated by

the culture. Children in San Pedro grow up to be capable and productive individuals, perhaps as well-adjusted as the average run of

human beings in most other cultures. But, as we shall see, they are far from devoid of fears, suspicions, and frictions. Part of the

explanation may lie in the rather sudden reversal of treatment experienced by children on graduating from infancy to childhood.

The weaned child who sees himself displaced by a nursing infant interprets the loss of constant attention as a mark of rejection and

makes his displeasure known through fits of petulance temper tantrums, and swift changes of mood. Busy with household duties, mothers

have little time for older children after tending to the needs of a breast baby. The next youngest child is not actually neglected,

but it can no longer be indulged in the style to which it has grown accustomed. Aggravated by the contrast, the child remains resentful

until the competing baby in turn is weaned, and the child, now third youngest, achieves a new adjustment by adopting an obedient role

toward the mother and a solicitous attitude toward the younger children. Parents and relatives do what they can to ease the frustration

of the recently weaned child by offering it fruits and confections and displaying tolerance toward its emotional outbursts. In good

time this tolerance will be withdrawn and sterner methods introduced to insure obedience.

By the age of five or six the child learns to submit to authority, to show deference to older members of the household, and to assume

responsibility for junior children. He finds that there is reward in duty, not so much in the form of approval as in the avoidance of

physical punishment and verbal censure.

|

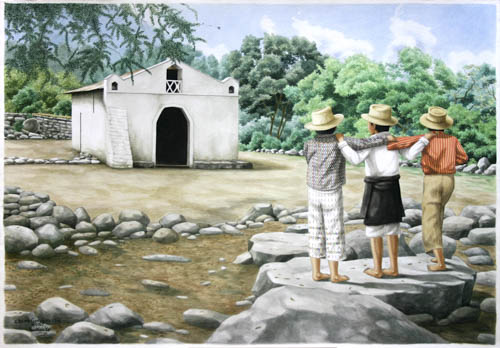

"Tres Amigos" (Three Friends). Chema Cox, 2000.

2. Early Training

Among our own urban families children seldom have occasion to help or to observe their fathers in their specialized occupations.

This is not the case in San Pedro. Indian children of both sexes get their training at a very early age by assisting their parents and through

games that prepare them for adult activities. Boys accompany their fathers to the fields as soon as their legs are sturdy enough to walk the

distance. Even before they are big enough to help actively with the crops, boys of five and six spend long hours in the fields frightening away

birds attracted to the newly seeded corn. They return to the village with a bundle of wild hay for the steer or wood for the family fire.

Before long they learn to wield the hoe and machete (all-purpose knife) and accompany their fathers on trips to market towns.

Between the ages of four and six, a girl may be given a few pennies and a dish and sent to the butcher to purchase a half pound of beef.

She helps her mother shell corn for the chickens. She sweeps out the house with a short-handled broom. She trails after her mother to the

lake, returning with a miniature water jar steadied on her head with one hand until she develops the required sense of balance. She kneels

before a small grinding stone to pulverize coffee beans. When she is seven or eight she begins to grind corn for tortillas. At this age,

too, she becomes a little mother to a baby sister or brother whom she carries about in a shawl slung over the shoulder.

Another educative mechanism is learning through play participation. Games supply diversion and recreation but by their nature they also provide

training for adult life. Children have a few toys such as dolls, dishes, tops, balls, and toy animals bought at markets. But, for the most part,

play materials are improvised from objects about the yard. A great many of the play themes are enactments of adult activities. Very young children

of both sexes play with dolls. A boy may pretend that the doll is his wife, instructing her to take care of the house while he goes off to work

or on a trading trip.

Among favored pastimes are the game of marketing, pottery fragments serving as money; mock religious processions with toy drums and dolls for saints;

and the game of sit-on-the mountain. The latter activity centers around the capture and punishment of a wrong-doer. A boy may be accused of having hit

his brother. He flees to the top of a volcano represented by a heap of earth. Unable to scale the volcano, the pursuers scoop away dirt until the culprit

topples backward from the undermined mountain. He is then whipped for his evil deed.

Little girls busy themselves in the yard with imitation household tasks, fetching water, washing clothes, tending baby dolls, and grinding corn on makeshift

stones. They make miniature belts by weaving corn leaf strips on a loom constructed of sticks and twigs. When they are older, but not yet adolescent, girls

enjoy the game of mock courtship. and elopement.

An outside observer paying close attention to informal play activities in San Pedro would gain a great deal of insight into the characteristic occupations

and preoccupations, attitudes and ideals of the adult community. Spontaneous enactment of real life activities and dramatization of episodes with moral

implications, such as the game of punishing the culprit, prepare children for adult responsibilities and shape their judgments to accord with those of

their culture. In this sense, pastimes and children's play amount to an informal but nonetheless real part of the educational system.

Until they are five, boys and girls do the same errands and play the same games. But at this age they become aware of sex differences. Boys begin to balk

at doing girls' work. A boy who willingly went alone to make purchases at a village store when he was four, at five demands that a girl companion go

along to carry the basket. This is now beneath his dignity. He will continue to clean the yard but will expect that his sister take over the task of

sweeping inside the house. Children learn what is appropriate to their sex not only through observation and imitation but also by suffering the taunts

of older companions. By the time they are seven or eight, boys and girls not only work at different tasks, but also play apart and attend separate

schools.

|

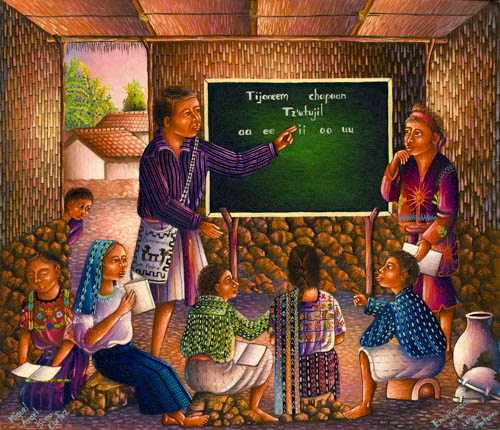

Now there are classes for the younger children in the Tz'utujil Mayan language, but when Benjamin Paul wrote this article, children were prohibited

from speaking Tz'utujil in the public schools. Painting, "Enseñanza en su Lengua Materno" (Teaching in our Mother Tongue), by Miguel

Angel Sunu Cortez. 2003. Collection: Rita Moran,

mayawomeninart.org

3. School Days

Federal law requires children to attend school until they complete three grades or reach the age of fourteen. Registration, however, is

not rigorously enforced by the native authorities in San Pedro who regard attendance as an obligation rather than as an opportunity. Most parents fail

to see practical value in formal education. They feel that as a result of schooling their sons may grow lazy and unaccustomed to field work. And they

ask ironically: "Will it help our daughters make better tortillas?" Most children enter school fearfully. The usual teacher knows the culture of the

Indian only superficially, has little regard for native custom and does not speak the local language.

Classes are held in a long portico-ed building facing the central square. The building is divided into a boys' and a girls' school each consisting of

three grades. Children are taught to speak, read and write Spanish, and are given instruction in arithmetic, history, geography, and such topics as

plants, animals, and parts of the body. Texts and class-room aids are scarce, and much of the instruction consists of learning by rote lists of

objects and definitions unrelated to daily experience.

here is little opportunity for a bright student to continue his education beyond the third grade. The cost of maintaining a child in a secondary school

away from home is prohibitive. On rare occasions one of the few Protestant families in San Pedro may send a son to a subsidized mission school where

the boy can complete six grades and possibly become a school teacher.

Girls rapidly lose the knowledge of Spanish acquired in school. They have little opportunity to use it and are ridiculed by other women of the town if

they try. Boys tend to retain their knowledge of spoken Spanish, finding it useful in commercial dealings with outsiders. But on the whole the San Pedro

child gains very little from school in proportion to the time he devotes to it.

The inadequate educational system is a heritage of the dictatorial regime of General Ubico. The present government of Guatemala, anxious to make rural

schools useful and purposeful rather than carelessly superficial, has recently initiated a project of teacher training and curriculum revision.

|