The Catholic church in San Pedro la Laguna. Evangelical Christianity did not exist in San

Pedro until the 1970s. Photo: Benjamin Paul 1941.

1. The Wooing Pattern

Boys have few occasions to meet girls. They do not mingle in social activities, and there

is no such thing as "dating" or calling on a girl. The established meeting ground is the lake shore and

its connecting paths, an area known as the playa. Girls go to the playa several times a day to fetch water.

Late in the afternoon boys return from the fields and station themselves along the water route waiting for

the girls.

Courtship conventions are standardized. The suitor may greet the girl, but he may not touch or detain her

as she descends for water. His chance comes as she ascends balancing a heavy water jar on her head. He steps

out of a by-path, grasps her wrist from behind, and the two remain standing as he delivers a set speech.

Indeed, the girl has little recourse but to remain attentive since movement or resistance would topple her

water supply. Perhaps that is why the boy does not try to interfere as she walks down the path encumbered

only with an empty jar; she might insist on continuing on her way.

Boys have few occasions to meet girls. They do not mingle in social activities, and there is no such thing as

"dating" or calling on a girl. The established meeting ground is the lake shore and its connecting paths, an

area known as the playa. Girls go to the playa several times a day to fetch water. Late in the afternoon boys

return from the fields and station themselves along the water route waiting for the girls.

Courtship conventions are standardized. The suitor may greet the girl, but he may not touch or detain her as

she descends for water. His chance comes as she ascends balancing a heavy water jar on her head. He steps out

of a by-path, grasps her wrist from behind, and the two remain standing as he delivers a set speech. Indeed,

the girl has little recourse but to remain attentive since movement or resistance would topple her water supply.

Perhaps that is why the boy does not try to interfere as she walks down the path encumbered only with an empty

jar; she might insist on continuing on her way.

Girls attract suitors when they enter adolescence. This may be as early as the age of twelve or thirteen, but

usually they are fifteen or sixteen when courtship begins. Boys are several years older when they start courting.

Wooing is a drawn out affair. No girl indicates consent the first or even the second or third time she is petitioned

on the playa. The usual courtship is prolonged over many months, occasionally over a year. There are good reasons

for the girl's hesitancy.

To begin with, the girl is frightened. She is young and has been shielded from boys since early childhood. The first

proposal on the playa is exciting and flattering but at the same time embarrassing. She is bashful and plays the part.

Her only reaction at first is shy passivity. She is immobile as long as her wrist is held and may not utter a word in

response to her suitor's pleas. The boy is not dismayed, for he knows that, he will have to repeat his plea day after

day before she overcomes her shyness. Sometimes a girl is so frightened by her first courtship experience that she drops

her water jug. But this seldom happens, not because it is considered bad taste, but because a broken jar is a serious

financial loss for which the girl will be severely scolded by her mother. Moreover, it is a sign of bad luck and the

girl may have to eat a fragment of the shattered clay pot to change her luck.

But even after the girl becomes accustomed to courtship she is slow to give her consent, for the prospect of married

life is not entrancing. Her burdens will increase, she will be faced with sex demands for which she is not prepared,

and she may fear that her mother-in-law will be a harsh taskmaster. Courtship by contrast is a pleasurable experience

and the girl has every psychological motivation to protract this episode as long as it is expedient to do so. Never

again will she feel so important. By withholding consent she exerts power over men, a privilege unique in her lifetime.

Nor is she disposed to encourage the first suitor; others may come along, and she may have a better panel from which

to choose.

If a girl is popular she may be wooed simultaneously by three or four swains. Among men there is no expectation of sole

possession of the girl during courtship.. If there are several contestants, each awaits his turn as she returns with

water. When one finishes his appeal the girl resumes her journey only to be stopped short by another aspirant.

Courtship gossip is a favorite topic of conversation among girls. They tell each other who is wooing whom, how

many beaux this and that girl has. Later in life women reminisce about their onetime popularity. Some will recall

that they were detained two or three hours in climbing the foot path, so many suitors did they have. Boys petition

only one girl at a time. If the girl persists indefinitely in maintaining her indifference, the young man may lose

hope and transfer his attention to another candidate.

|

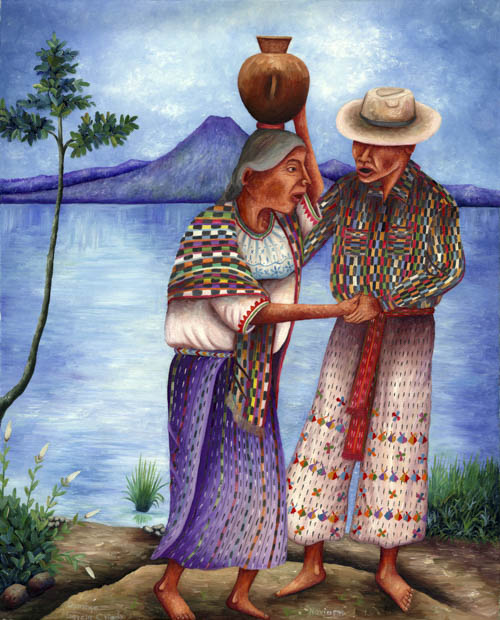

"Noviasgo" (Courtship). Painting by Domingo Garcia Criado, 2001

A. Courting Speech. What do the boys say as they stand behind a girl clasping her wrist? They consume

little time in romantic adulation and avowal of eternal passion. Such notes may creep in, but major attention is centered

on allaying the standard fears attending marriage. The petitioner realizes what every woman knows, that the bright promises

of today may soon fade before the harsh realities of wedded life, that she may suffer from neglect and even from want, that

she will amount to little more than a servant in another household.

This then is the content of a typical courting speech: "I come to court you. I love you. Let us be married. You are I grown

up now. It is time for you to take a husband. I will buy clothes for you; I will purchase earrings and bright shawls. My mother

is a kind woman; she will not be cross with you. My father is a good man; he is not severe. We have enough corn; we have enough

beans. My mother will give you whatever you need; you will get everything. Why not get married? All women get married. I am a

good man; I will not get drunk and beat you. I will come with my parents to your house, and they will speak to your parents.

Or if you wish, we can elope. My family will receive you well. They will not scold you. I will buy you skirts and blouses."

Variations on this theme may extend the proposal speech for an hour or more. It is much the same on following days. At first the

girl does not venture to reply. When she does, her attitude is invariably negative. She will give reasons for not marrying: "I

am too young. My mother would get angry." And she will give reasons for not marrying him in particular: "You are an idler and

cannot support me. Your mother is mean. Your father is cross. You are too young (or too old). They say you deserted your first

wife." And so on.

B. Winning Assent. Far from discouraging the boy, these strictures arouse hope. She now answers. She sounds unwilling and

skeptical, but that is the characteristic response of a girl in San Pedro. A yielding attitude would mark her as brazen and immodest,

might even scare off her suitor. Perhaps she is little different from the American girl who chides, "You do not love me." Both are

bidding for reassurance. The San Pedro suitor goes on dispelling her doubts. The girl continues to voice her distrust. She never

says "Yes." But she can indicate assent by indirection, by the passive act of retaining a symbolic gift which is an indispensable

item of courtship.

This stylized gift, known by the Spanish term Brenda, is a small packet tied up with colored yarn containing two old Spanish coins,

now handed down as heirlooms. It is presented to the girl during courtship on the playa. The boy makes no vain effort to persuade

her to accept his Brenda. He drops it into her blouse at the back of the neck. She cannot extract it without loosening her clothes.

Perforce she takes it home with her. She probably does not mention the event to her parents but she sends the coins back to the boy's

house, usually by a younger brother or sister. The coins are never kept the first or even the second time they are slipped into her

blouse. To accept them at once would betray an improper lack of reserve. The boy continues his pleading on the playa. When at last

his Brenda is not returned, he knows that he has gained consent even though the girl may have said "No" earlier that same day. The

next day he detains her by the wrist as before, but only to discuss the method of marriage, whether it is to take place formally

through negotiations between their parents or informally by elopement.

Some of the more sophisticated suitors supplement their courtship conversations, which are always carried on in the Indian vernacular,

with formal love letters, written in their own hand or by a more literate friend. These, too, conform to pattern but the romantic note

is given more stress, as in the example that follows:

Unforgettable Senorita: As I take up my pen to greet you, I hope this humble letter finds you and your worthy family in good health and

spirits. And now you must know that I am mad about you. You are the light of my life. This is my second letter, and I beseech you to be

so good as to reply so that I may know your answer and that you are thinking of me. I want to marry you, but you have told me you would

never get married. No, my pretty one, the opposite is true. Let us get married. We will live in peace and happiness. Never will I do

you harm. I will buy you whatever you wish. Don't think I will not do this. I am a good worker. That is all. Your attentive servant.

(Signed)

Such letters are ignored or draw negative answers. If no confidante is at hand to read the message for her, a girl unfamiliar with Spanish

may burn the letter unread lest it fall into her mother's hands and lead to argument.

|

"La Pedrida," (The Request for her hand in Marriage). Painting by Matías González Chavajay, 1999.Collection: Rita Moran,

mayawomeninart.org

2. Arranging the Marriage

If the girl indicates that she wishes to marry according to custom, the boy informs his family, and a long series

of formal negotiations is begun be-between the two families. An actual case will best illustrate the procedure.

After four months of courtship on the playa, Tono won Anita's consent and so informed his parents. Tono and his father went to

Anita's house in the evening. Anita's father asked them to return on another occasion, since he could make no decision before

speaking to Anita who was hiding away at the moment. The second call was made by Tono's father and an older married brother.

This time they were told that no answer could be given until they brought along an outside witness; interested relatives could

not always be trusted to act in good faith. Several days later Tono's father and mother, accompanied by a venerable citizen

named Milcher, made a third call, but only after sending word of their intended visit so that they might be well received. They

were served coffee and bread purchased for the occasion. Milcher opened the formalities by making a ceremonial speech asking

for Anita on behalf of the absent suitor and the visiting parents. The girl's father replied with another conventional speech.

Then the boy's father and the two mothers spoke in turn. Finally Anita was called in and asked whether she wished of her own

free will to marry Tono. She did. Her father then instructed the petitioners to return in three months.

As they were leaving, the visitors left a cash gift of two dollars so that the parents might buy some costume items for the bride.

The girl's father tried to refuse the money, remarking that he was not selling anything, but the go-between, Milcher, left the cash

on the man's lap, insisting that it would be useful in purchasing earrings or some other little thing for the girl. Each week

thereafter the suitor's family sent Anita a five-cent cake of soap.

After the stipulated three months had elapsed, the boy's family dispatched a message stating that they were coming for the bride on

a specified evening. The girl's family replied that they would be ready. The delegation for this fourth and final visit was made up

of Tono's parents, an older brother, Milcher, and the latter's wife. This time the visitors were given bread and hot chocolate, a

drink reserved for ceremonial occasions. After eating, Milcher made a formal speech. Then the bride's father spoke and wept. The

remaining three parents as well as the wife of the witness each spoke. The hostess handed over her daughter's clothes to Tono's

mother; everyone bade everyone else goodnight; the bride cried and said goodbye to her weeping parents; and they, in turn, told

her to be well behaved as she reluctantly left the house.

The party now proceeded to the home of the waiting groom where all were served coffee and bread. Milcher instructed Tono and Anita

to drink from the same cup and eat from the same dish and concluded the formalities of the evening by offering them solemn advice.

He reminded them of their duties as man and wife and warned them against quarreling. It was late in the evening but in the kitchen

women of the house were busily grinding corn for festive tamales. Anita wanted to help with the grinding, but Milcher's wife told

her to make her husband's bed instead. Tono's mother showed her where they would sleep.

Early next morning gifts of food were sent to Anita's ' I family, a basket of bread, chocolate, and two pounds of sugar. Bread and

chocolate were also sent to Milcher and, his wife in partial payment for his good offices in acting as witness and intermediary.

More food was sent at noon, two cooked turkeys, and two baskets of tamales to the home of the bride, and a cooked chicken and a

basket of tamales to Milcher's house. But in addition, Milcher and his wife were invited to eat the midday meal with Tono's family.

Everyone kissed the hand of Milcher and of his wife in respectful greeting. Again Milcher enjoined the newlyweds to eat from a

common dish, and again he delivered words of instruction both before and after sitting down to eat. In honor of the occasion gifts

of meat, tamales, and bread were sent to the homes of all the relatives of the groom.

This case differs in detail from others, but the essentials recur in most instances of marriage by formal petition: a series of visits

to the home of the girl, always at night, by a group made up of the suitor's elder kinsmen; the involvement of a respected third party

to act as go-between and to give moral and practical instructions to the bride and groom; presents of food sent by the boy's household,

hospitality extended by the girl's parents; the demonstration of sustained good faith evidenced by repeated gifts of food, trinkets, or,

as in this case, soap over an extended period of time; the minor role played by the boy and girl; weeping on the part of the bride and

her parents as she leaves to take up a new life. Sometimes there are witnesses on both sides. In many cases the petitioning parents bring

along bottles of liquor. Willingness of the bride's parents to join them in drink is construed as an augury of eventual consent.

Preliminary negotiations are always carried on under cover of darkness. People say they would be ashamed to do otherwise. In effect this

means that the public should not become aware of the petitioners' intent lest their efforts result in failure and the petitioners lose

face. Moreover, the practice of evening calls guards against the interference of malicious gossip which might prejudice the outcome.

Seldom are marriages recorded in the civil registry or sanctified by a Catholic priest. However, it can be seen that the participation of

the honored outsider is the social and moral equivalent both of a legal act and a holy sacrament. Should trouble arise between the partners

in marriage, kinsmen can be counted on to use their influence in settling the difficulty. Having been active parries to the agreement,

they hold themselves responsible for the success of the match.

Should the girl leave her husband, her in-laws can exert pressure on her parents to persuade her to return. If she is maltreated or neglected

by her husband, she can appeal to her parents to take her back or defend her cause in case of a civil suit. Or the officiating witness may

be called on to compose differences between the spouses of the two families. In short, the elaborate negotiations and interchanges between

the two contracting bodies of kinsmen and the involvement of an outside arbiter not only serve to impress the couple with the seriousness

of their new responsibilities, but also set up moral machinery to help stabilize the union. This machinery does not always hold the marriage

together, but it helps. The system relies more on force of parental authority and fear of shame than on independent judgment and the dictates

of conscience.

|

"Se Caso Unica Hija" (The only daughter got married). Painting by Diego Isaias Hernández Mendez, 2002.

Sometimes it is the groom who moves in with his wife's family. Such cases happen quite frequently owing to special circumstances

which favor such an arrangement. A girl may consent to marriage only on condition that she and her husband live with her parents. If the boy

is especially smitten with the girl and can overcome the protestation of his own parents, he complies. But more often the reason is one of

expediency. The boy may be an orphan living with relatives or a laborer originally from a neighboring village and may welcome a home with

in-laws whose land he can work for a living. Or may come from a poor home and look forward to a greater inheritance if he establishes himself

as a good worker in his father-in-law's household, especially if the wife has few brothers.

But whatever the motive, the marriage is again arranged by relatives and witnesses, there is sharing of food and drink, and the newlyweds receive

lectures on duty and deportment. Initiative in the negotiations remains with the family of the groom who go by night to the home of the girl and

who deliver the boy rather than call for the girl. Before the marriage is consummated, the groom shows his good faith and demonstrates subservience

to his in-laws by sweeping their patio in the morning and bringing to them a load of freshly- cut firewood in the evening. The formalities are less

complex than in the more conventional type of marriage described above, but the family obligations and the influence of the witnesses are similarly

designed to make the marriage last.

As a matter of fact this alternate pattern is the more likely to insure domestic stability. Adjustment is now the problem of the incoming husband

there is less likelihood of friction between a man and his father-in-law than there is between a girl and her new mother-in-law. The two women are

thrown into close and continual contact, and, if the new-comer is not by nature accustomed to complete submission, tension may well build up to the

point of eventual explosion. But a man working for his father-in-law has more freedom of movement if not of decision; as a man he has contacts

outside the home to engage his interests; he does not venture to compete with his mother-ill-law in directing the routine duties of her daughter,

and he has every reason to avoid trouble with his father-in-law lest he lose his means of livelihood and jeopardize his eventual share of the

inheritance.

These then are the two types of family-sponsored marriage in San Pedro. The less frequent form in which the boy takes up his residence in the girl's

home may lead to greater harmony but the reverse arrangement remains the more orthodox, since it fits in with traditional inheritance practices by

which land is transmitted from father to sons. Moreover, it is consistent with the spirit of a male-dominated culture, that the burden of adjustment

be thrust upon the woman.

But most marriages today conform to neither traditional pattern. Most girls prefer to elope, even at the cost of antagonizing their parents. This

always involves conspiracy I against the girl's parents and at least the tacit consent of the boy's parents who must receive the girl into their home.

3. Elopement

On their final day of courtship on the playa the boy and girl who plan to elope agree on an hour and signal. The girl goes home with her

jar of water and keeps herself busy at the usual tasks to forestall suspicion. Around bedtime or later she finds a pretext to leave the house, and takes

along a bundle of clothing secretly prepared beforehand.

Once outside, she gives the signal, usually by tossing a pebble, to inform the boy that it is she and not another woman of the house. The boy knows there

is no surer way of precipitating trouble for himself and the girl than to reveal his presence to the wrong person. When he hears the signal the nervous

suitor comes out of his hiding place and the two scurry away as fast as darkness will allow, the girl falling behind the boy and carrying her own bundle

of clothing. They try to reach the protection of the boy's home before being overtaken by the girl's parents. With a head start they generally succeed.

The parents of the girl will infer what has happened as soon as they discover her absence, but they may not know in which direction to give chase. From

earlier rumors reaching them from the playa, the parents may know that their daughter has a number of suitors and who they are, but they may not be able

to guess at once which of the contestants affected the capture. Nevertheless, they rush around frantically, arousing the interest of their neighbors

who are eager to take part in any excitement. Angry parents frequently bring suit against their daughter and her "captor" as soon as they establish

their whereabouts. The daughter is never returned to her parents, but they gain a minor moral victory in having the court exact a fine from the

offending couple.

|